State looks to DMV, DHHS for help with anti-prison gerrymandering

by April Corbin Girnus, Nevada Current

CARSON CITY–In an eleventh hour attempt to pull the state into compliance with a 2019 anti-prison gerrymandering law, the Nevada Departments of Motor Vehicles and Health and Human Services are trying to identify the last known addresses of thousands of inmates.

Duane Young, the policy director at the governor’s office, detailed the effort in a response dated Thursday to the ACLU of Nevada, which warned in its own letter to the governor earlier this month that the state was putting itself at legal risk by only reallocating half of the state’s inmate population.

A law passed in 2019 requires Census data be adjusted so prison inmates are counted as residents of where they last lived, rather than as residents of the jurisdictions where their prison cells are located. Counting prison inmates as residents of the municipalities and counties where prisons are located artificially inflates the voting power of those areas, an outcome known as prison gerrymandering. The areas that benefit are typically rural.

More than 10 states have passed legislation ending prison gerrymandering, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

A representative of the Nevada Department of Corrections in late October told lawmakers that it was only able to adjust half of the 12,214 people living at its various facilities.

More than one-third — 35.4% of inmates — had no prior address on file with NDOC. Another 5.9% had in-state addresses that were not complete enough to be used. An additional 7.3% listed addresses that were out of state and therefore could not be reallocated.

NDOC cited myriad reasons for their lack of data, including that the information needed from inmates was voluntary and many refused to provide it. The governor’s office said in its brief letter Thursday that the DMV and DHHS have experienced similar challenges as NDOC but have “been able to make strides in validating additional addresses.”

The letter did not specify how many additional addresses have been identified.

Holly Welborn, policy director for the ACLU of Nevada, said those numbers, when made publicly available, will help determine whether the state has truly made a “good faith effort” to comply with the anti-prison gerrymandering law. But she maintained that the “laundry list of excuses” provided by NDOC originally were not sufficient.

NDOC also referenced homelessness, transiency, mental health and substance abuse, and technical database compatibility issues as contributing factors to their compliance rate.

Welborn said the ACLU is working with national experts to determine what level of response is expected and acceptable, recognizing that some inmates will not be able to be reallocated for legitimate reasons.

A special legislative session on redistricting looms over Nevada and is expected to begin as soon as Friday. Democratic legislative leaders have already unveiled their proposed maps for the state’s four congressional districts, 63 legislative districts and 13 state board of regents districts.

Prison gerrymandering is one of many redistricting issues expected to arise during the special session. Other issues will include partisan gerrymandering and minority representation. Whatever maps are ultimately approved will be used for elections held over the next decade.

Even with only half of the state prison population being reallocated, the impact of the 2019 law is noticeable.

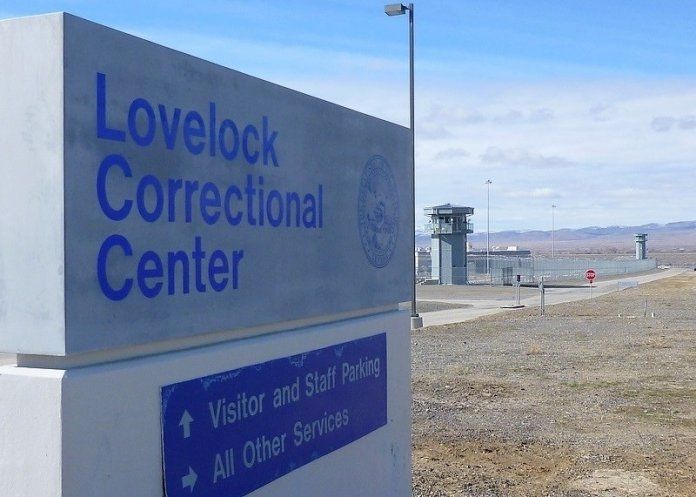

Pershing County, where Lovelock Correctional Facility is located, saw its population adjusted down by 9.7%.

White Pine County, where Ely State Prison is located, saw its population adjusted down by 4.9%.

State Senate District 19 and Assembly District 36, which include the part of Clark County where High Desert State Prison is located, saw their populations adjusted down by 2.4% and 3.45%, respectively. Those districts are currently represented by two Republicans, state Sen. Pete Goicochea and Assemblyman Gregory Hafen.

Legislative Counsel Bureau materials on the impact of the prison inmate reallocation did not include a complete breakdown of which NDOC facilities housed the most inmates with no last known addresses. But High Desert State Prison has the largest overall inmate population, according to NDOC reports.

Inmates who were not reallocated to their previous communities will still be counted as residents of the prison. In other states with anti-prison gerrymandering laws, people who cannot be reallocated are not factored into redistricting data at all, a Legislative Counsel Bureau staffer told lawmakers last month.

According to NDOC reports, one quarter of inmates are serving indeterminate or life sentences; 43% are listed as having their longest sentence be under 10 years.

Those men and women, Welborn said, deserve to be counted as residents of the communities where they once resided and are likely to return.

Ending prison gerrymandering was one of several criminal justice reforms that Nevada lawmakers have embraced in recent years. In 2019, the Legislature passed a law automatically restoring voting rights to approximately 77,000 formerly incarcerated people. This year, approximately 33,000 formerly incarcerated people were identified by the DMV as potentially being eligible to have their driver’s license reinstated, thanks to a law passed during the 2021 session.

Nevada Current is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Nevada Current maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Hugh Jackson for questions: info@nevadacurrent.com. Follow Nevada Current on Facebook and Twitter.